Mito nosso de cada dia: PIGMALIÃO

|

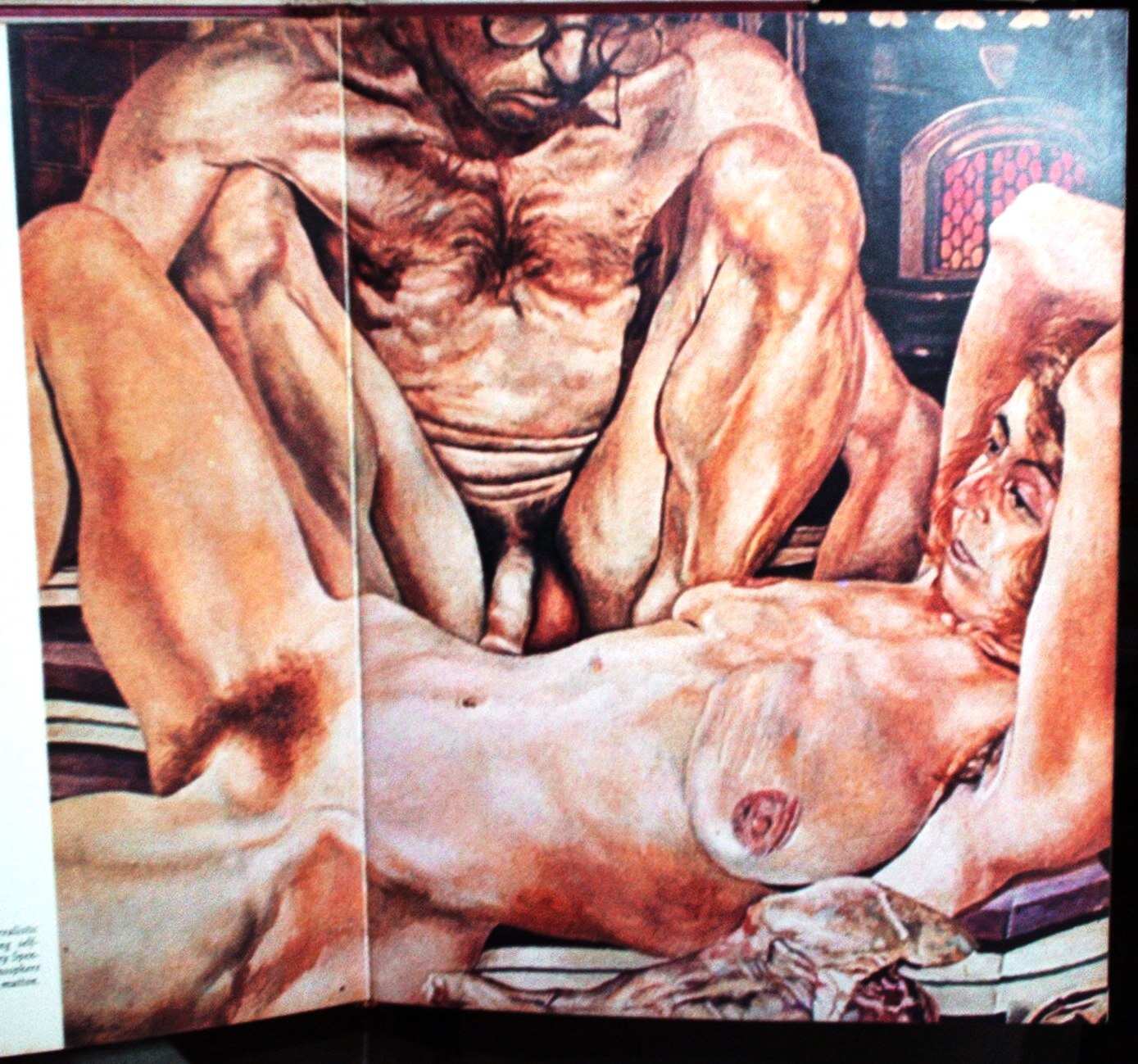

| Louis-Jean-François Lagrenée: Pygmalion and his statue |

O mito de Pigmalião (em grego Πυγμαλίων) está muito mais atual do que imaginamos.

Pigmalião era um talentoso escultor que desiludido com as mulheres, criou uma imagem de mulher em marfim, para fazer-lhe companhia. A figura esculpida era Galatéia – escultura de extrema beleza, trabalhada com primores de arte que parecia um ser vivo. O escultor se apaixona por sua obra e convive com ela como um ser vivo: dá-lhe presentes e carinhos. Entretanto, insatisfeito e desejando a perfeição real, implora a Afrodite que lhe permita encontrar uma mulher igual à estátua de marfim. A Deusa atende o pedido, mas do seu jeito de Deusa. Quando Pigmalião volta para casa, encontra a estátua de marfim com vida. A estátua agora mulher torna-se sua esposa. Da união carnal, nasce um filho, Pafos, epônimo da cidade cipriota de Pafos, e uma filha, Metarme.

A mais antiga fonte da lenda é uma obra de Filostéfano de Cirene (fl. séc. -III). Mas o mito de Pigmalião tornou-se mais conhecido a partir da obra de Ovídio, "Metamorfoses" (10.243-97).

O nome "Galatéia" foi utilizado pela primeira vez por Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712/1778) no drama musical "Pygmalion", de 1762.

O mito foi tema da primeira ópera de Gaetano Donizetti, "Il Pigmalion" de 1816; poemas de John Dryden, 1703 e Carol Ann Duffy, 1999; peças de teatro como Conto de Inverno (1623) de Shakespeare, também a de William Gilbert, em 1871 e Bernard Shaw, em 1914; balé do coreografo Marius Petipa e do compositor Nikita Trubetskoi, em 1895. E no balé" Copélia". Na Literatura, o mito está presente em "Frankenstein", de Mary Shelley (1818), "O Homem Positrônico", de Isaac Asimov e Robert Silverberg (1993) e "Galatea 2.2", de Richard Powers (1995). E na história de Carlo Lorenzini de 1883, que se tornou animação de Disney em 1940, "Pinóquio".

No Brasil, uma obra do maestro e compositor português João Victor Ribas trouxe o mito de Pigmalião à Corte de D Pedro II, ao que parece com toques de uma certa cor nacional. A cantata alegórica intitulada "O templo da glória ou O novo Pigmalião", dedicada a Imperatriz Thereza Christina para homenagear o nascimento do príncipe Afonso em l845, foi apresentada no Teatro São Pedro de Alcântara. Essa obra musical de canto e dança teve coreografia de Luigi Montani, dirigidas por Francesco York, e compunha-se de várias peças de dança e música apresentadas pelos corpos de balé e de ópera do teatro. Na parte musical, um coro feminino representava "As Musas", um masculino representando "Os Gênios". Nos papéis principais, Augusta Candiani representava "A Glória", o tenor Archangelo Fiorito, "O Templo" e o tenor Angiolo Grazziani, "O Gênio Brasiliense".

Interessante pensar no mito no contexto daquele país de segundo reinado buscando seus ares de nação. O que seria "O gênio brasiliense"? Uma metáfora da utopia de uma nação? Desejamos uma nação? O mito de Pigmalião parece ainda presente.

Vivemos ainda sob o mito de Pigmalião. Fazemos nossas esculturas, castelos, jardins suspensos no céu e nos apaixonamos perdidamente por eles, obras do nosso esforço, desejo e vontade. Pedimos aos Deuses que nos acalme transformando a beleza idealizada em salvação real.

Mas nenhuma Afrodite nos dá mais ouvidos.

Só resta encarar a realidade ou ficarmos na solidão do estúdio (ou do computador ou do país) onde construímos nossas artes.

Pigmalião está muito mais na nossa vida do que ousamos pensar. Melhor nem pensar... Melhor ler Ovídio.

The Story of Pygmalion and the Statue

Pygmalion loathing their lascivious life,

Abhorr'd all womankind, but most a wife:

So single chose to live, and shunn'd to wed,

Well pleas'd to want a consort of his bed.

Yet fearing idleness, the nurse of ill,

In sculpture exercis'd his happy skill;

And carv'd in iv'ry such a maid, so fair,

As Nature could not with his art compare,

Were she to work; but in her own defence

Must take her pattern here, and copy hence.

Pleas'd with his idol, he commends, admires,

Adores; and last, the thing ador'd, desires.

A very virgin in her face was seen,

And had she mov'd, a living maid had been:

One wou'd have thought she cou'd have stirr'd, but strove

With modesty, and was asham'd to move.

Art hid with art, so well perform'd the cheat,

It caught the carver with his own deceit:

He knows 'tis madness, yet he must adore,

And still the more he knows it, loves the more:

The flesh, or what so seems, he touches oft,

Which feels so smooth, that he believes it soft.

Fir'd with this thought, at once he strain'd the breast,

And on the lips a burning kiss impress'd.

'Tis true, the harden'd breast resists the gripe,

And the cold lips return a kiss unripe:

But when, retiring back, he look'd again,

To think it iv'ry, was a thought too mean:

So wou'd believe she kiss'd, and courting more,

Again embrac'd her naked body o'er;

And straining hard the statue, was afraid

His hands had made a dint, and hurt his maid:

Explor'd her limb by limb, and fear'd to find

So rude a gripe had left a livid mark behind:

With flatt'ry now he seeks her mind to move,

And now with gifts (the pow'rful bribes of love),

He furnishes her closet first; and fills

The crowded shelves with rarities of shells;

Adds orient pearls, which from the conchs he drew,

And all the sparkling stones of various hue:

And parrots, imitating human tongue,

And singing-birds in silver cages hung:

And ev'ry fragrant flow'r, and od'rous green,

Were sorted well, with lumps of amber laid between:

Rich fashionable robes her person deck,

Pendants her ears, and pearls adorn her neck:

Her taper'd fingers too with rings are grac'd,

And an embroider'd zone surrounds her slender waste.

Thus like a queen array'd, so richly dress'd,

Beauteous she shew'd, but naked shew'd the best.

Then, from the floor, he rais'd a royal bed,

With cov'rings of Sydonian purple spread:

The solemn rites perform'd, he calls her bride,

With blandishments invites her to his side;

And as she were with vital sense possess'd,

Her head did on a plumy pillow rest.

The feast of Venus came, a solemn day,

To which the Cypriots due devotion pay;

With gilded horns the milk-white heifers led,

Slaughter'd before the sacred altars, bled.

Pygmalion off'ring, first approach'd the shrine,

And then with pray'rs implor'd the Pow'rs divine:

Almighty Gods, if all we mortals want,

If all we can require, be yours to grant;

Make this fair statue mine, he wou'd have said,

But chang'd his words for shame; and only pray'd,

Give me the likeness of my iv'ry maid.

The golden Goddess, present at the pray'r,

Well knew he meant th' inanimated fair,

And gave the sign of granting his desire;

For thrice in chearful flames ascends the fire.

The youth, returning to his mistress, hies,

And impudent in hope, with ardent eyes,

And beating breast, by the dear statue lies.

He kisses her white lips, renews the bliss,

And looks, and thinks they redden at the kiss;

He thought them warm before: nor longer stays,

But next his hand on her hard bosom lays:

Hard as it was, beginning to relent,

It seem'd, the breast beneath his fingers bent;

He felt again, his fingers made a print;

'Twas flesh, but flesh so firm, it rose against the dint:

The pleasing task he fails not to renew;

Soft, and more soft at ev'ry touch it grew;

Like pliant wax, when chasing hands reduce

The former mass to form, and frame for use.

He would believe, but yet is still in pain,

And tries his argument of sense again,

Presses the pulse, and feels the leaping vein.

Convinc'd, o'erjoy'd, his studied thanks, and praise,

To her, who made the miracle, he pays:

Then lips to lips he join'd; now freed from fear,

He found the savour of the kiss sincere:

At this the waken'd image op'd her eyes,

And view'd at once the light, and lover with surprize.

The Goddess, present at the match she made,

So bless'd the bed, such fruitfulness convey'd,

That ere ten months had sharpen'd either horn,

To crown their bliss, a lovely boy was born;

Paphos his name, who grown to manhood, wall'd

The city Paphos, from the founder call'd.

Metamorfoses, de Ovidio, livro X